SPACE IS NOT EQUAL.

There’s a quiet mistake that keeps repeating itself whenever people talk about systems. It sounds sophisticated on the surface, almost scientific, but it rests on a shallow idea that the best system is the one that distributes space evenly, that stretches the field until every player has room, and that more room automatically means better football. It’s comforting because it’s measurable. You can draw it. You can divide the pitch into corridors and zones and convince yourself that you’ve solved something fundamental.

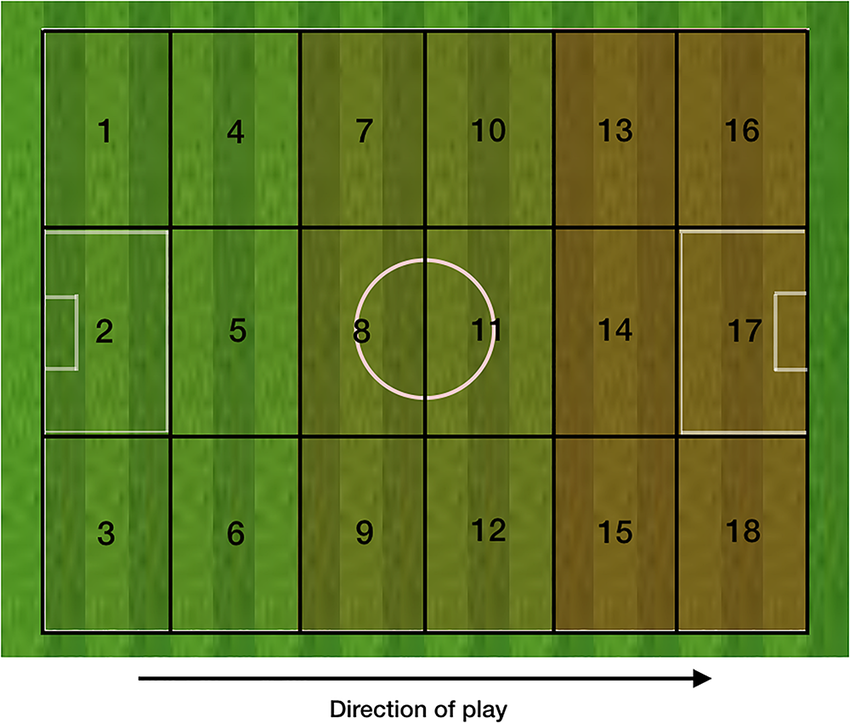

Space does not carry the same value everywhere. Ten meters near the touchline do not threaten the same things as ten meters between the lines. When we draw the pitch as a grid, we imply equality where none exists, and systems built on that assumption end up optimizing order instead of danger.

A football pitch is finite. Fixed. About 105 meters long and 68 wide. That fact alone should already raise suspicion about any idea built on endlessly “creating” space. You cannot create it. You can only decide where it matters.

The problem is that we talk about space as if it were neutral. As if ten meters were ten meters everywhere. But anyone who has actually lived inside a match knows that this isn’t true. Space does not behave the same way across the field. It does not threaten the same things. It does not ask the same questions of the opponent.

The most common explanation for why space matters is that it gives time. More space, more time. More time, more options. It sounds reasonable, and sometimes it even looks right. But it breaks down quickly once you stop watching the ball and start watching the defenders.

A player can have time and still be harmless.

What turns a moment into danger is not comfort. It’s leverage.

That leverage comes, first and foremost, from position. Specifically, from being central.

Central positioning quietly changes everything. From there, the game opens up. Not because there is more space, but because there are more directions that matter. Left and right are still available, but now forward becomes a threat. The goal becomes a real reference, not an abstract one. A shot does not need to be perfect. A half yard is enough. A small shift of the ball can be decisive.

This is why central players create hesitation. Pressing centrally is never automatic. Step out too early and you expose what’s behind you. Stay passive and you allow the attacker to turn. Defenders are forced into waiting, and waiting is already a form of losing control.

This is where the old idea that space equals time equals options begins to feel insufficient. Options are not created by time alone. They are created by angles. And angles multiply when you are central.

Numbers matter here too. One extra player between the lines doesn’t just add a passing option. It forces decisions. Two defenders might be occupied by one body. An entire line might shift for a threat that hasn’t even touched the ball yet. The ball can move slowly while the damage is already done.

This is why some of the most influential modern teams feel crowded rather than expansive. When you watch sides shaped by coaches like Fernando Diniz or Henrik Ryström, the point is not disorder. It’s density with intent. Numbers placed where angles already exist. Relationships prioritized over territory.

Central space has diminishing returns. It does not need to be large to be valuable. A few meters are enough because the the angles to goal are already favorable. Vision is wide. Options are immediate. Threat is constant.

Wide space works differently.

Out wide, space finally behaves the way people often describe it. Here, distance matters. In isolation, more space clearly favors the attacker. A one versus one with room to run is a different duel than a one versus one near the touchline with no depth behind it. The same applies to two versus two situations. As space increases, defensive coordination becomes fragile. Cover distances grow. Timing becomes harder to manage.

This is what width is for. Not for comfort. Not for standing still and surveying the game. But for confrontation. For forcing defenders to defend while moving, without cover, without certainty.

Seen this way, the idea of the best system becomes simpler, not more complex. It is not the system that maximizes space everywhere. That only spreads threat thin. It is the system that understands where space converts into danger, and where it doesn’t.

Central areas reward numbers and angles.

Wide areas reward isolation and distance.

In the end, the best systems in modern football are not defined by how evenly they stretch the pitch, but by how deliberately they concentrate danger. They place the best players centrally, where angles to goal are richest and decisions carry immediate consequence. They commit numbers inside, not to dominate possession, but to force hesitation and compress the opponent around the most valuable spaces on the field. And then they release space wide, not as decoration, but as a weapon, creating isolations where distance tilts the duel toward the attacker.

This is not a stylistic preference or a theoretical ideal. It is a recognition of how the pitch actually works. Where angles multiply, numbers matter. Where isolation appears, space matters. Systems that respect this relationship do not just look coherent. They endure, because they align structure with threat, and threat is what ultimately decides matches.

Once you start watching football with that in mind, certain things become impossible to ignore. Why the best players drift inside even when the wing is empty. Why teams that look cramped can feel impossible to press. Why width without purpose feels harmless. And why so many decisive moments come from places that looked ordinary until they weren’t.

Nothing about the game has changed.

Only the way we choose to see it.